Visual cultures of occupation in wartime China

Much of north, east and south China was occupied by the Japanese military, or by Chinese “client regimes” backed by the Japanese military, in the period between December 1937 and August 1945. While the brutality, deprivation and violence of the occupation have often been the focus of the academic literature on this period, scholars are increasingly looking at the various ways in which Chinese people who lived under occupation expressed themselves. There is also a growing awareness in the field of modern Chinese history that the Chinese regimes and organisations which emerged under Japanese domination in this period are worthy of study in their own right, and can tell us much about both the nature of the wartime experience, and about the “political culture” (and cultural politics) of occupation more generally.

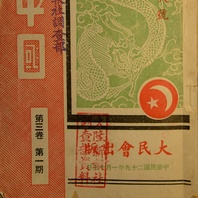

This case study includes examples of visual cultures generated in areas of China occupied by Japan between 1937 and 1945. It mainly includes materials produced by “collaborationist” Chinese administrations. These include the Provisional Government of the Republic of China (PGROC) in north China (1937-1940); the Reformed Government of the Republic of China (RGROC) in east China (1938-1940); and the Reorganised National Government of the Republic of China (RNG) which was founded in March 1940, when it subsumed most existing “client” states, and which only ceased to exist in 1945.

Explore Themes

Return to the capital

In March 1940, a new occupation state was founded in wartime China, when a group of defectors “returned to the capital” (huandu) of Nanjing to — in their view — restore the Nationalist Chinese government that had fled from the Japanese at the end of 1937. The occasion of this “return” was marked by a series of public celebrations but also by a great deal of internal debate about what this new “occupation state” would look like. The huandu period might be said to have lasted until November 1940, when a new treaty was signed between Nanjing and Tokyo, and the “occupation state” was formally recognised by the Japanese. The huandu of 30 March would remain an important commemorative date in Nanjing through until the end of the war.

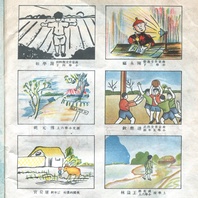

Rural Pacification

The qingxiang (Rural Pacification) campaigns were introduced by the Japanese and the RNG in the summer of 1941, as a response to communist resistance in rural Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces. The campaigns continued in various guises through until 1945. Rural Pacification was important for the RNG as it enabled this “client regime” to extend its influence into the countryside. It also enabled RNG cadres to re-imagine rural China under occupation in an overtly Nationalist fashion.

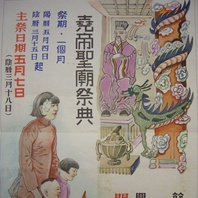

Entertainment in occupied China

Despite (or perhaps because of) the Japanese occupation, the commercial entertainment industry thrived in wartime China, especially (though not exclusively) in Shanghai. The film industry, print culture, and commercial music all continued firstly in gudao Shanghai (i.e., that part of the city not occupied by the Japanese), but also, after December 1941, throughout Shanghai as a whole.

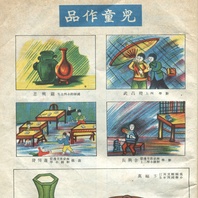

New Citizens Movement

The New Citizens Movement (Xin guomin yundong) was initiated in January 1942. It called for the rejuvenation of a revolutionary spirit among occupied China’s youth, and the “liberation” of Asia by the Japanese. It was also a performative movement, in which youth were expected to display their loyalty to the Republican Chinese state under occupation. The movement was inspired by the rhetoric of the May 4th movement, but also by patterns of youth mobilization developed in other parts of the Axis world (namely Japan and Germany).