“Angel of Peace (heping tianshi )”:

Icon of Occupation in Wartime China

![Henry Fehr's Allied War Memorial listed here as the 'God of Piece' [sic], at some stage in the 1920s](https://modscotcast01.blob.core.windows.net/cotca/2018/07/VISCHI-0001-5b4609a3c6df0-418x600.jpg)

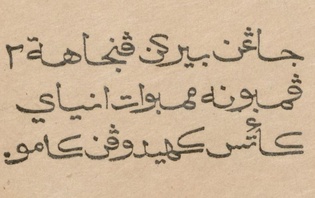

Henry Fehr’s Allied War Memorial listed here as the ‘God of Piece’ [sic], at some stage in the 1920s (Courtesy of the Historical Photographs of China Collection, University of Bristol).

The angel is featured overlooking a bucolic scene of water buffaloes, ox herds and willows in an unattributed drawing entitled “Dong Ya heping zhi leyuan” (Paradise of East Asian peace). This image was featured in the pictorial Dong Ya lianmeng huabao (Toa Pictorial) 1.4 (June 1941).

Following the Japanese invasion of China in 1937, however, Fehr’s Victory was given a new significance for a variety of Japanese client states. Even prior to the establishment of the Reorganised National Government (RNG) in 1940, for example, the figure was worked into occupation propaganda in eastern China, with the notion of an “angel of peace” resonating with both Japanese client states set up in 1938 which promoted a negotiated peace with Japan, and with Wang Jingwei’s “Peace Movement” (Heping yundong) after 1939. Fehr’s figure was appropriated in the same year as into the cover design for one of the main vehicles for the Peace Movement in Shanghai, the periodical Gengsheng (Rebirth).

Under the RNG, Fehr’s figure was transformed into an “goddess of peace” (heping nüshen), and was regularly featured in depictions of the Shanghai streetscape in RNG-sponsored graphic art. Indeed, the RNG “angel of peace” motif into the visual landscape of the RNG well beyond Shanghai, and wherever references to anthropomorphised peace were useful. In some instances, children dressed up as the “angel of peace” when publicly commemorating important dates on the RNG calendar. Elsewhere, Fehr’s monument was re-imagined in rural Chinese landscapes by RNG artists as a harbinger of RNG notions of peace.

Unnamed boy dressed as the “angel of peace” (heping tianshi) during celebrations to mark the first anniversary of the founding of the Guangdong Provincial Government under Japanese occupation, May 1942.

Ironically, with the “return” of the foreign concessions to RNG rule in 1943, the Japanese ordered that symbols of Western imperialism be removed from Shanghai’s streets. This, of course, included Fehr’s Allied War Monument (with Victory herself being removed, but her plinth left intact). The “angel of peace” thus provides us with an insight not simply into the eclectic origins of many of the symbols adopted by the RNG, and the creative ways in which this regime appropriated pre-war symbols of peace into a wartime cultures of occupation. It also illustrates the limits of RNG autonomy when it came to constructing visual cultures under foreign domination.

[1] Robert Bickers, “Moving Stories: Memorialisation and its Legacies in Treaty Port China”, in Max Jones, et al (eds), Decolonising Imperial Heroes: Cultural Legacies of the British and French Empires (London: Routledge, 2016).

[2] Paul Bevan, A Modern Miscellany: Shanghai Cartoon Artists, Shao Xunmei’s Circle and the Travels of Jack Chen, 1926-1938 (Boston: Brill, 2016), 267.